Grantourismo! Traditional Mexican Food

September 21, 2010 – by Terence Carter

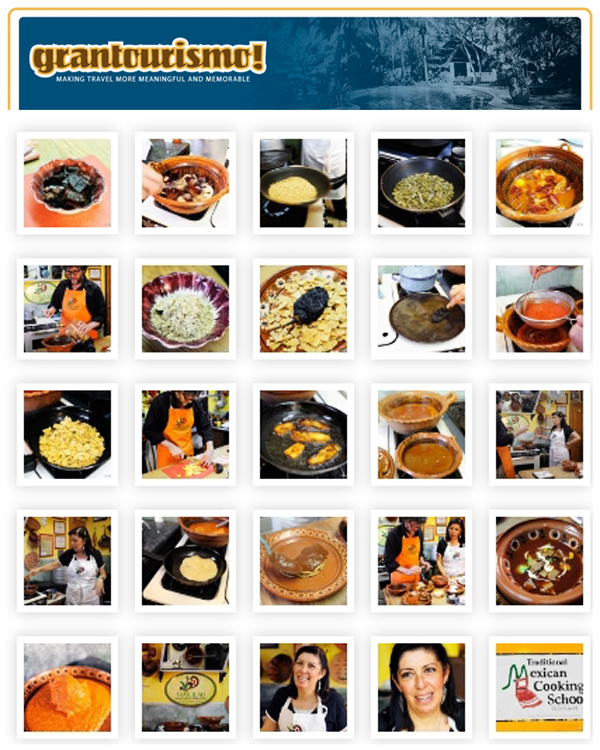

“The focus of my school is traditional Mexican food, not the cuisine of chefs!” Marilau Ricaud, the owner of the Marilau Traditional Mexican Cooking School in San Miguel de Allende, says as she hands me an apron. “I felt San Miguel was lacking in good restaurants to eat Mexican food and I think it’s rare for foreigners to get the opportunity to eat in a Mexican home, so I decided to teach home-cooked food.”

“The focus of my school is traditional Mexican food, not the cuisine of chefs!” Marilau Ricaud, the owner of the Marilau Traditional Mexican Cooking School in San Miguel de Allende, says as she hands me an apron. “I felt San Miguel was lacking in good restaurants to eat Mexican food and I think it’s rare for foreigners to get the opportunity to eat in a Mexican home, so I decided to teach home-cooked food.”

And this was exactly what I was looking for. Not fancy Mexican food. Nor Tex-Mex, which in my opinion, is only good for placing speed humps in front of hangovers late at night. Or blunting their impact the next morning. San Miguel de Allende, for all its picture-postcard beauty, did not have a cuisine scene that could rival that of Oaxaca, arguably Mexico’s best eating city, so all the more reason to learn how to cook Mexican ‘at home’.

Today I’m learning just three dishes, recipes that Marilau learned from her mother and grandmothers: Sopa de Tortilla (Tortilla Soup), the pre-Hispanic dish of Pollo en Pipian Rojo (Chicken in a spicy pumpkin seed sauce), and Sarapitos (plantains in tortillas with mole sauce).

I had some reservations. I love my own recipe of Sopa de Tortilla and wasn’t keen to find out that I had been making it wrong all those years! I dislike chicken, unless it’s in Thai food (Laab Gai preferably or chicken satay) or a plump Bresse chicken whose skin is filled with truffles and butter before a stint in the oven. Plantains are best left for monkeys and mole is a horrid concoction best used to disguise mal carne (bad meat). What was I thinking?

Pollo en Pipian Rojo

We begin the class by prepping the second course, Pollo en Pipian Rojo, as it will take longer to make. “Cut the chiles, open them up, and pull the vein and seeds out,” Marilau instructs me. “But never rinse them as water reduces the flavour. The most important thing is to pull out the vein, the spiciest bit, but not scratch the inside of the chile. With chiles, there are two types, fresh and dried, and there are different techniques for each, you can’t work in the same way for each one.”

Marilau asks if I eat pork lard, because many participants don’t. “Mexicans never use olive oil – it belongs to the history of Spain, not Mexico. When the Spanish came, Mexico didn’t have olive oil. Mexicans always use pork lard,” she says.

Marilau shows me how to toast the chiles – for less than ½ minute – “simply to wake up the natural oils” – then we add the onions, chicken stock and salt (preferably rock salt), and put a lid on it all to simmer for 10 minutes. After we will blend it.

Next we toast the almonds, then the sesame seeds (when they pop they’re ready), and blend these together. Traditionally Mexicans used a metate, a large sloping stone, to grind grain and seeds, but Marilau opts for a blender because she wants people to feel comfortable doing this at home. Next we blend the pumpkin seeds separately into a powder as well. Explaining the consistency, Marilau says “We’re not too attached to texture in salsas in Mexico. We like smooth salsas and that’s because of our French ancestry.”

We return to our pot on the stove and spoon the contents into the blender to blend the hot chiles and onion to a smooth paste. “We always serve this salsa with meat,” Marie-Claire says, as we strain the sauce. “The pre-Hispanic people always used meat, pork and duck, never vegetables, though we could add potatoes if we wanted, or cactus, which is very traditional.”

“We’ll simmer it for 5 minutes more,” Marilau says, asking me to add the powdered seeds and whisk carefully. “You can smell the change in the aroma as you add the seeds, can’t you?” The seeds add an extra taste, but while they season they also thicken. Mexicans never use corn starch or flour, Marilau says. The sauce now has complexity and a nutty flavour and the fiery heat of the chile has calmed down like a wayward child after dinner. We add the pumpkin seed powder next.

“If you want it even thicker, let it simmer more on a light boil,” Marilau advises. “Then add chicken stock. With the meat, you can cook it any way you like. In Mexico we normally like to boil it, but you can also bake, steam or grill it. Just don’t season it with as the salsa gives it enough flavour.”

Sopa de Tortilla

My favourite Mexican soup is Sopa de Tortilla. I hadn’t had a decent one on this trip so I was keen to see how this turned out…

First we prep our ancho chile, toasting it a little in a pan, then putting it in hot water. “Never boil chile, and never burn chiles either,” Marilau advises, showing me how to turn the chile constantly. “You can tell when it’s ready by the smell – the smell is different when it’s untoasted and toasted. Mexicans always use their nose when they cook!” When it’s toasted, we put the chile in hot water and put a weight on top of it. We could also snip it open to allow some hot water inside to reduce the spiciness a little. We put a lid on the pot for 15-20 minutes till it’s soft enough to blend.

“Soups in Mexico are always light in consistency and texture, due to the weather,” Marilau says, as we chop the tomatoes, a slice of onion and a clove of garlic. “Just a small amount of garlic and onion,” Marilau advises “This is not European cuisine!” Next, we add one cup of chicken stock, the soft chile – “never touch the inside of it!” she warns – and put it whole into the blender, blend it all together, then strain it just as we did with the salsa. We add salt and pepper and we simmer it all. When the soup has lots of colour, it will be ready…

Next we prep the garnish. We add vegetable oil to a pan, some small pieces of corn tortillas (“We only use corn tortillas here,” Marilau says. “You’ll only find flour tortillas in the USA and around the Mexican border.”) Traditionally, tortilla strips are used, but Marilau prefers squares because they stay on the spoon. “The taste is what’s important,” she says.

We deep fry the tortilla pieces, and as they should be crispy, not soggy, they should be served alongside the soup with the other garnishes. I think I’ve overcooked them, but Marilau says they’re fine. “In Mexico, we think it’s important for people to eat the soup how they like it,” she explains, “So all the condiments are served on the side and people can add things to suit their own tastes.”

We chop Manchego cheese (cow’s cheese) into cubes (Marilau warns not to use Spanish goats cheese and to use Gouda if you can’t get Manchego); we put sour cream into a dish (Mexicans never use regular cream, she says); we slice an avocado, scoop out the seed, and cut the avocado into cubes (or slices); and we roughly chop cilantro and put everything on a plate to serve beside the soup.

Sarapitos

Marilau has already made a batch of mole sauce that she uses for the dessert to her own secret recipe for which she uses 30 different ingredients. “There are 1000s of different mole recipes and just two, from Oaxaca and Puebla, use chocolate,” she tells me. “You know, I once had an American student who walked out because I refused to put cheese in mole!”

First, we fry whole tortillas lightly on each side. Marilau uses plantains not bananas, and explains the difference. The plantains are hard to peel, unlike a banana. They also smell sweet and starchy. We slice them thinly, then fry them in vegetable oil, turning them over when they’re golden and dark around the edges. When they’re ready, we put the bananas in the tortilla with a little mole, fold the tortilla in half and serve more mole on top, sprinkling some sesame seeds on at the end.

My Verdict

The Sopa de Tortilla has a delicious flavour but is a little mild for my taste. Marilau suggests I add another chile to the recipe. I also like the idea of DIY condiments on the side. It makes more sense. I used to serve the garnish already on the soup. The pre-Hispanic Pollo en Pipian Rojo is fantastic as well and making the sauce was instructional in terms of seeing how the flavours develop complexity and how the initial overt heat of the chili was tamed during the process. The Sarapitos are delicious. I’m in shock as I finish the plate in seconds. Had every mole sauce before this one tasted that bad? On this trip they certainly had. Marilau’s mole sauce was a revelation.

After the class, Lara and I stroll back to our casita along hilly cobblestone streets with ramshackle unrestored houses, where hardly any expats seem to live. As we pass shops, locals are buying last-minute ingredients like corn tortillas for their lunch, the most important meal of the day. We can pick up the aromas of soup simmering in homes. Marilau will already be enjoying her meal with her family. We now know where the best food in San Miguel de Allende is to be found. And it doesn’t come with an English-language menu, orange cheese, or the ‘ding’ of a microwave.